It was a Monday. A minute among the few of his three hour break between shifts. The kitchen was a mess this morning, and the rush had left him empty. He left his hands in his pockets as he walked.

First came the wagon, tilting with the ruts in the trail. The whole of it shimmered and dissipated and was there again. He blinked to confirm what he was seeing, but as they got closer they weren’t solid per se, but they were no longer a broken transmission. His heart climbed into his throat, or maybe it was his stomach. There was an overwhelming urge to hurl. He’d always had guts and a stubborn sense of pride. Maybe that’s all that kept him from vomiting.

A man drove the wagon and a girl rode behind that man. It was clear that the man saw him and chose to ignore him. But the girl was different. Her eyes blazed wide as she watched him. He thought she was lovely and, but for her translucence and the cold sweat running down his arms, something akin to fancy arose in his chest alongside the sick. But the couple in the wagon passed without words. He caught his breath only to find another shade. At the sight of the shape on the hill, he looked around him for the markers of a highway, maybe a portal. And then he checked his own hands to see if they too were fading away.

It was a deacon that passed next, wearing the fear of god in his eyes. The man of god was a squirrelly fellow—his eyes darting around as though something weighed heavy on his soul, and the punishment he had pretended to administer for so many years was just around the corner for him. For whatever fear that shadow carried with him, there was still a glint of hard hatred in his eyes. A crinkle in the lips, a sign of distaste. The deacon made the sign of the cross and glared at him one last time before he faded away in a mirage.

And then came the boy on the horse. He wasn’t a boy exactly. Somewhere near a man. The boy was dirty and smiled from his place in the saddle. There was a gun on his hip. A hat on his head. The hat was folded and crunched but he thought it fit the young man well.

By now, he was used to the order of things, this strange passing. He looked freely at the boy on the horse and smiled, but his stomach turned again when the young cowboy spoke.

“Who-are you?” the boy on the horse asked.

He stopped. Tried to think of what to say, but found his thinking useless.

“Just a cook,” he said.

The boy spit, and smiled again. Despite the grime around his eyes, his ears, and his mouth, the boy did not smell. And he liked the boy’s smile. It had no hatred in it, no mockery. It was the smile of someone thrilled in life, someone who’d steal the cookies with you and split them fairly at the rendezvous. And who’d laugh a laugh unfit for polite society no matter where he found himself.

“You got any food?”

He shook his head.

The boy on the horse stopped smiling as he looked out over the hills. The sun was going down.

It’d be the dinner rush soon, but he’d forgotten.

“Where are we?” the boy asked.

“I-,” it was hard to say, but he didn’t feel like lying, “I don’t think we’re in the same place.”

The boy on his horse looked at him. In a glance he was older, weary; there were lines hidden in that grime on his face. The young man in the hat spurred his horse on. There was blood on the back of his shirt.

He left his hands in his pockets as he walked back down the hill, down past the houses, over the crosswalk and under the overpass. Though cars roared on their way, he didn’t feel like there were any people there. When the door closed behind him, and the stainless steel was once again under his eyes, the metal cool against his fingers, he asked himself the question the boy had posed on the hill.

Josefina arrived. She washed her hands and turned to see him.

“Hey.”

“Hi,” she replied.

“You see me yeah?”

“…yes?”

He nodded.

The work started. The tickets came in. And he floated away in another rush, reacting to the sounds and the calls, the heat of the ovens, the knife in his hands. He forgot it all by closing. Just felt like a dream.

He can still remember what the nurse looked like. His father said that she was pretty, and that she was being nice to him, so it wasn’t so bad after all.

He remembered the room too. A chemical smell and the lights on the ceiling shining their reflections on the floor. All the while, his dad kept saying to him, “Don’t forget.”

“Don’t forget now.”

And then on that last day when his dad gave him a present—fancy that—Dad was the one dying and he got a present out of it. Even better when he pulled that fresh bill out of the bag. Now that was a smell. Beat the hell out of a hospital trying to stay clean. He looked up from the ball cap to see his daddy’s grin.

“Ah,” he said, “ain’t so bad now is it?”

His dad died the next morning, and he was supposed to be at school. He wanted to run away, run for the hills, for the sea—wherever—but whenever he gave that any thought, he heard his father’s words, “don’t forget now.”

With those words, his dad was back and they were walking up the hills and seeing the houses, or holding hands in the shadows of the giants, with all the busy folk wearing coats and ties and looking very serious.

“There’s magic here,” he would say, “don’t forget now.”

When his dad would say that, he felt the magic in the very ground and in the air around them. He felt a witness to majesty then.

And even when his cousins moved out to the valley, he and his mom stayed on. He remembered the words. Even when his mom lost her way, and the hills were singing sweet lullabies drawing him from the streets that seemed so dirty now, he remembered the words. Even when life seemed to crash and burn and nothing seemed to work out at all. Three times, he’d bought the ticket.

Once for a bus, and he’d been there in the dark of early morning, waiting to board. He heard his father’s words and turned home.

Another for the train. In the crowded breath of a station on a warm afternoon, he stepped backwards from the crowd and disappeared in the city.

The third was the hardest. It was spur the moment. He stood on the pier in tears. He boarded the ferry and looked back at the city in long rays of the evening light. It was his favorite way to see the city. He cried quietly as the ferry pulled away, and he felt himself losing everything that he was. When it came time to get off, he didn’t.

He was old now. Walked with a limp. But he wore the same hat. Walked in the shadow of giants to go to work, smiling now as he remembered his father’s words. He was the only one left here now. He had some kin somewhere in the valley but he liked it here. This city was only place where felt like the concrete was alive, as if the whole place might heave up and wash into the sea, and all the folks on the streets would go on as though it were just part of the plan. He was the only one left here now. He had some kin somewhere in the valley but he liked it here. Things were a little dark now, but he still believed.

Now when the sea called, or the hills beckoned, he waved them off and reminded them he couldn’t walk well anymore anyways. And now when that fear crept up in him, when he wondered whether his whole life of waking days might’ve been wasted here and harder here for the troubles he’d seen and lived through, he squeezed the hat that rested on his nightstand and remembered his father’s words.

The solar visor shielded them from most of the light, but the old star was brilliant—he smiled that he still had to shield his eyes. The crew took note of the flares they saw leaping and arching from their place on the deck. He watched it all with the measured despair of someone battling a long disease. There was nothing to do but fold his hands behind his back. His smile fell away.

With the Sun behind them, the tremors that cracked in his mind settled, and the crumbling buildings there clung on to their foundations for another flight—for one last trip. And everything but the stars around them played out in hues of violet as they passed Mercury. Then they saw it:

He felt the collective hush as the entire crew held their breath. Many, he knew, had only stories of this place. It was harrowed in tales of horror and beauty. There were whispers of atrocities and tales of heroes told across the galaxy. What none of those tales included, he felt, were the days. The nights. They missed what it was like to breath there, to stand and walk and look around. The ship pulled closer to the little planet. No one made a sound, but he saw each of them shift in their seats or on their feet, unconsciously reaching out to it.

Precious little marble, he thought. It was a wording, and a way of looking at things like planets and stars far too big for any human to ever grasp that he had held on to ever since he was a child pressing his face against the portholes of different star ships. The bald head of his first mate half-turned to address the landing conditions.

They glided into the atmosphere during sunset.

“Mike,” he said, “if you’ll indulge me.”

“Aye Captain.”

He and the first mate donned wet suits. Ancient designs. There were suits now that could push off the stinging cold, but the captain was not looking for that comfort today, and he was thankful his first mate, his old friend, was of like mind. They pulled the surfboards down from the walls of their cabins. Ran the beach in bare feet, exhaling in short little bursts of air that required no tanks, no pressurizations. They paddled out into the rolling surf.

There were other seas on other planets—closer, warmer—in violets and greens, and one even in red. But the Captain wanted one more here.

They surfed until the sun was low. There were still sea birds above the beach, and a harbor seal that watched them, its black eyes blinking at them from here it hid in the sea. The captain sat on his board, with his legs in the water and watched them, and a question haunted him: where will they go?

He and Mike walked the beach toward the river, drinking in the hues of green as the winds and the waves played to their ears. He watched his breath. He wanted to slow down. He wanted to hang on to this, to make it last a little longer. He could feel the evening slipping away. He stopped, and out of reflex, Mike stopped beside him without a word.

“You know,” he said, and was shocked at the cracking of his voice. Emotion did not usually find its way through his throat. But as he watched the rays of light play over the cliffs, there was no helping it.

To his credit, his first mate didn’t flinch.

“Yes captain?”

“Part of me wants to stay.”

“Could awhile, sir.”

The Captain nodded, but staying a day or two and jetting off wasn’t what he had in mind. In a romantic dream, he walked the surface of the earth in its dying days until the end. What he wouldn’t say aloud, was that he wanted to go with it. Walk until his feet bled, wanted to cross every square inch of desert and mountain. Wanted to swim in redwoods and salt and rain. Wanted to gather the whole thing up in his arms as the darkness fell. Wanted to smell every morning until the last morning—hold on to every sensory impulse until the last sunset. In his dream, he was the last apostle to the mother of them all.

But he would fly off and leave her tonight, so he sat in the sand until the stars appeared above him, before he rose and returned to his ship.

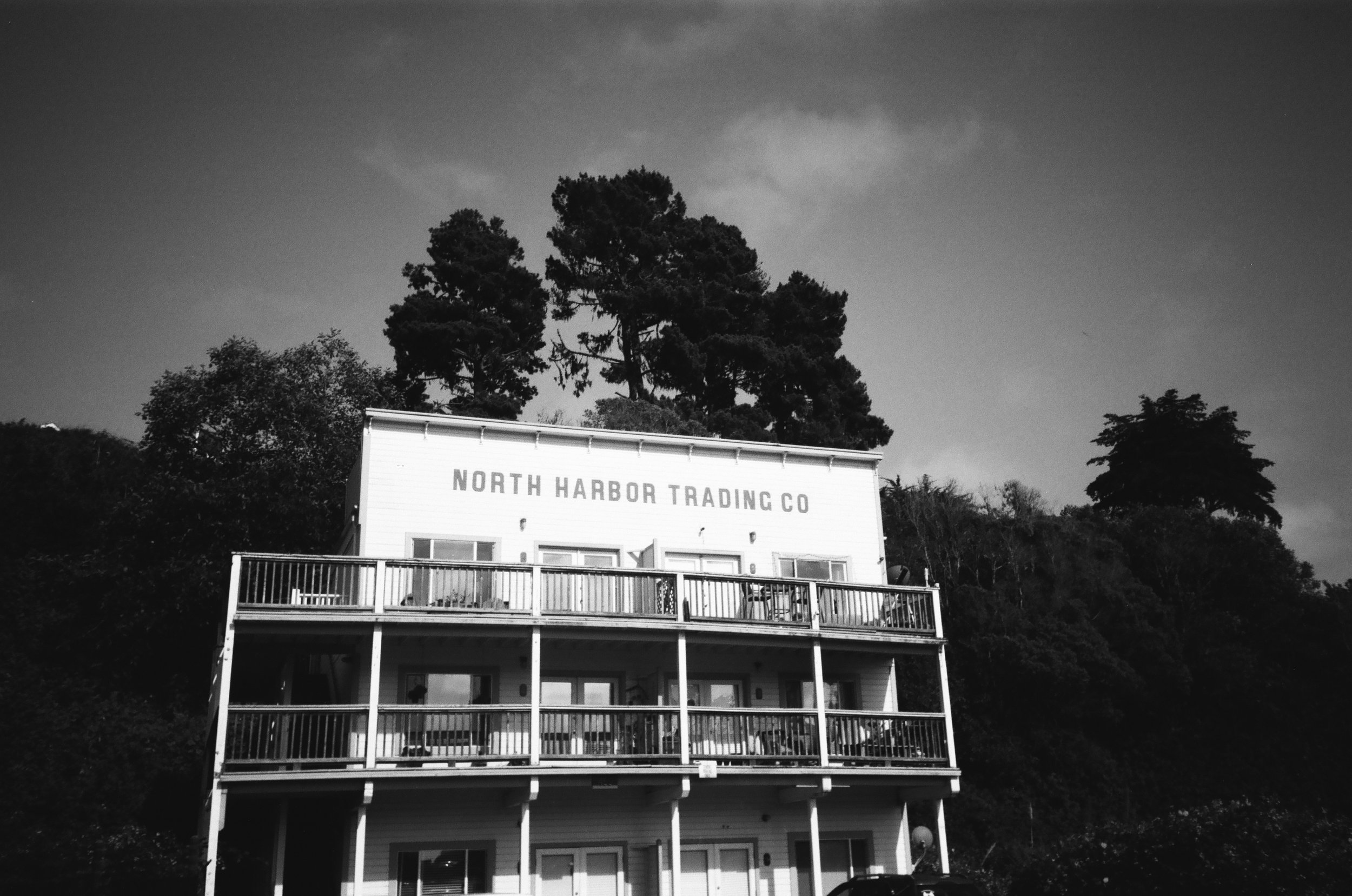

Beyond the doors of the North Harbor Trading Company, the world sat on shelves. Bottles of elixirs, two for every affliction, reflected light on the far walls. Squat your love or embolden it. Sip actual liquid courage. Dot your wrists with pheromones of the elusive midnight jaguar and watch your luck turn. There were walking sticks by the door that warded off thieves, and bits of garland you could tie to your belt or wear on your hat that matched the weather to your mood. And there was a girl at the desk whose eyes gave you hope, but she was the only thing you couldn’t take home. Beyond a curtain was another room, cast in shadows. Inside, lanterns threw yellow light on dull blades. The weapons were much like everything else in that store. They looked normal. Simple wooden handles, and dull metals, yet here were world cleavers. Usurper knives that toppled emperors. Saber blades for slaying generals. There were poisons and pains and shirts and axes that toppled giants. Everything carried destiny. Everything warned of it.