A good game comes about simply.

First, you remember yourself. You figure out where you’re at, and consequently who’s sitting across from you. One breath’ll do. There’s no need to find some inner child. They’re not gone. At any moment, you can leave behind the shell you’ve built up being hurt.

Then: forget yourself.

Add a pinch of mischief, a volley of snark, and you’re off to the races.

You don’t even need rules.

There’s a tree half-fallen on the way. There are ticks clinging to stalks in waiting. There’s a thunderous sea taking half the space of the world (in case you haven’t noticed). The trail is half washed-out and dangerous. Divers leave ropes tucked into the cliffs. Engines pulling metal on rubber atop asphalt roar behind you. You have to run across to get here. You have to. You have to pass that line of death and escape into the relative quiet of wind and moss and trees you expect might be thousands of years old. The earth is worn down to the roots by the winds and you think it might all go at any second. Still, you look out at as sunlight filtered through clouds strikes the heaving sea and you have to smile at it all breathing alongside you. Each bend makes you want to run, to fly through the trails and lift off like the gulls, like the osprey, like little killdeer floating along the surf, but you walk. You walk to taste it.

A hundred dollars won’t go far here.

A thousand just won’t do.

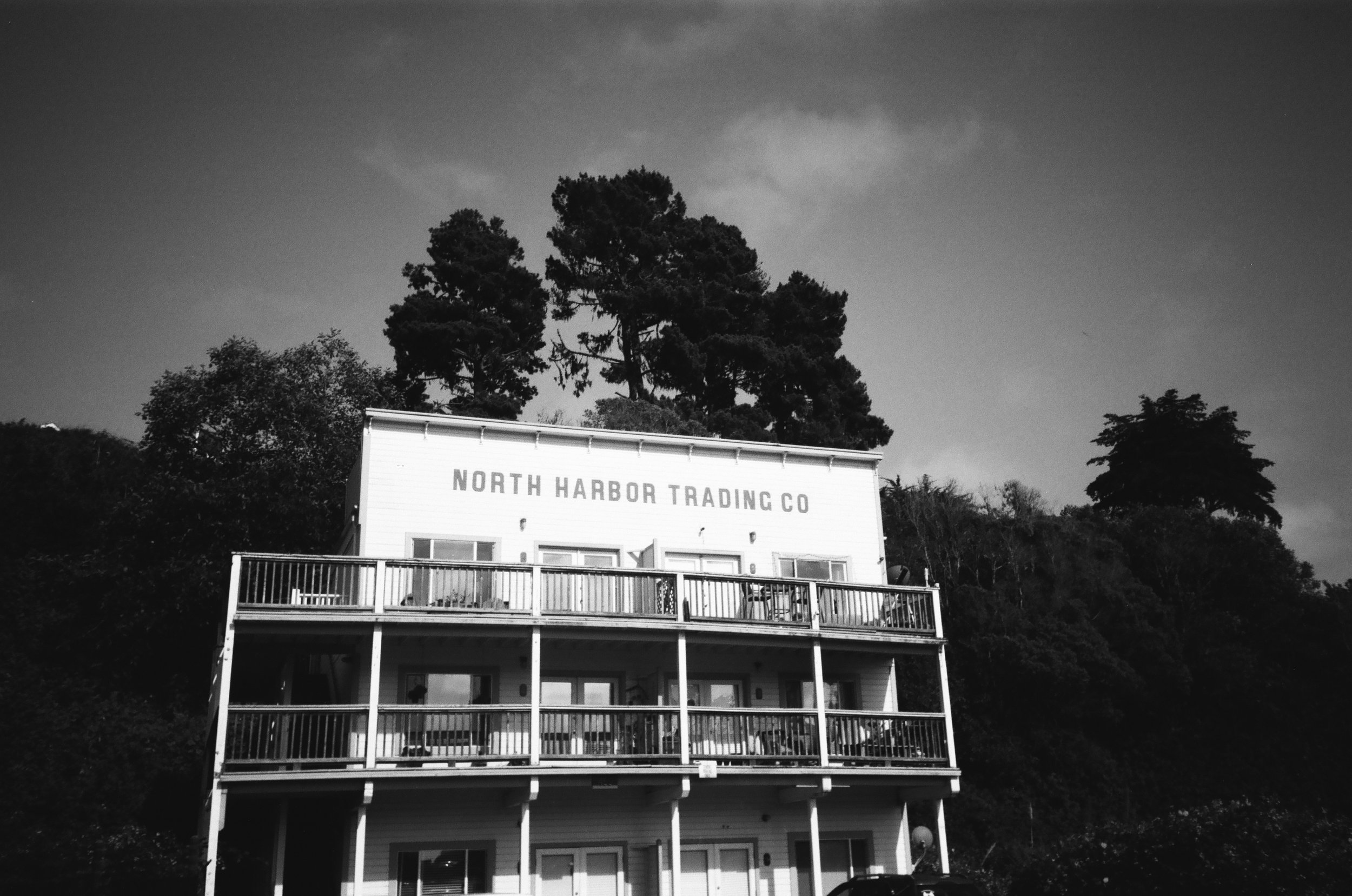

Donning the aisles

Are rosy, wild smiles

And the plate glass came from Zarkdon II.

Storm winds moan all they like,

Ravens cackle on the eaves

While inside ray guns hum

That don’t kill a thing.

Stones that shine

Grab the eye

And children wonder freely

“Look here, into this looking glass, “the old shopkeep says,”

“At the cross of magic and science.”

Her knitted hat draws them in,

Her lighted eyes stays them,

And inside the miracle of life

Bids them come.

A switch, a spring,

The movement here is that of life,

And the light in her eyes passes to them as they watch the toy come alive—

ALive!

Leap about, and dance

DAnce!

How much?” The man asks,

Him grinning as believers do

“Four dollars, no tax” she says

And it seems a small thing, a small price to pay

For wonder.

This witch’s hovel is well-lit

On the edge of the world.

We go down the way past the the adventure store, to where the jam shop watches the headlands. The trail is half-flooded with runoff. The boys run; we yell at them not to run. “Stay away from the edge,” and “watch your footing” and they ignore us and go on to the staircase or the cave and the sea keeps on despite them screaming into the wind and laughing. I don’t know if the sea notices them or they notice the sea or if the two interact as playmates.

It’s warm enough, and our shoes are more or less dry, and the hills don’t seem impossible now that the boys can run up them themselves. We’re not tired or defeated by our lives back home. We’ve missed it here.

How many times have I thought that it’s this place? Down to the washed asphault, the little retaining wall and the few steps at the bank on the corner. I put it to the air: the presence of the sea and the cliffs. And the weather! It feels like at any moment the world might turn. I consider what it would be to stay there. I watch the people working the restaurant and the cafe. I watch the old locals, all artists or ag folk or both, who dress to themselves and wonder at none, because they are the interesting ones. They ignore me, or maybe they never even see me, and they don’t know that I’m one of them—only a step from joining their ranks for my entire life. That there are thousands upon of thousands of me’s that are just like them. That our places are no less beautiful in their own ways. It always helps to look at them, because then I am confronted with the truth: that for all the details, the feeling of the place always comes back to whom you’re walking with. Hands in my pockets, I might walk these streets by myself for a moment, and I enjoy it only because I know that around the corner two pairs of rubber sneakers are thundering out of the toy store, wielding more life than the town has ever seen, and behind them a pair boots carrying along the pretty girl who’d I’d’ve been searching for my whole life had I taken that step.